By MARK PEARSON Follow @Journlaw

A media scrum gathered outside a Sydney court this morning where Harriet Wran – the youngest daughter of the former premier of New South Wales Neville Wran who died this year – was charged with murder and other offences.

I will not go into the details of the crimes Harriet Wran is alleged to have committed with a co-accused – to which she is pleading not guilty – but they relate to the death of 48-year-old Daniel McNulty and the stabbing of another man, Brett Fitzgerald, at an inner Sydney apartment block on Sunday night.

Celebrity is a driving news value and leads reporters into dangerous territory in cases like this, as co-author Mark Polden and I explain in the fifth edition of The Journalist’s Guide to Media Law, to be published later this year.

Order through Booktopia at http://www.booktopia.com.au/the-journalist-s-guide-to-media-law-mark-pearson/prod9781743316382.html

I have already seen numerous images of the accused – which is problematic if identification of either accused has any likelihood of being at issue in the trial. Any potential impact on witness identification – or any indication of the guilt of an accused – can be deemed sub judice contempt of court over which publishers can face hefty fines and jail terms if a court deems their coverage represented a real risk of prejudice to a trial.

The Latin phrase sub judice literally means ‘under or before a judge or court’ and applies to the period during which there are limitations placed on what the media may report about a case. The restrictions start from the moment someone has been arrested or charged.

In this case that period is well and truly under way, with court proceedings having commenced.

The courts have attempted to balance the competing rights and interests of those involved in court cases and those reporting on them by restricting what may be published about a case while it is before the courts. The restrictions are considered necessary to avoid ‘trial by media’, where free speech interferes with the usual safeguards of the legal system with dire consequences for the case at hand and for the public confidence in the administration of justice.

The practical concern the courts have here is the potential influence such a media trial might have on prospective jurors (and, to a lesser degree, on witnesses). The fear is that their judgment (or testimony) might be tainted by media coverage of the case before or during trial, to ‘poison the fountain of justice before it begins to flow’, as one judge expressed it in Parke’s case in 1903. The courts place stringent tests on the admissibility of evidence and respect certain rules of procedure known as ‘natural justice’, protocols that have no tradition in media coverage.

There is a ‘public interest’ defence – but that is highly unlikely to apply in a case where the only real public interest is the fact that one of the accused happens to have come from a famous family.

When deciding whether a publication is in contempt, the courts look to its ‘tendency’ to interfere with pending proceedings. As the NSW Law Reform Commission expressed it in 2000:

To amount to contempt, a publication must be shown to have a real and definite tendency, as a matter of practical reality, to prejudice or embarrass particular legal proceedings.

When considering whether the publication has the ‘tendency’ to interfere with proceedings, the courts gauge the potential effect of the sub judice material, not whether the material actually caused harm, with the test applied at the time of publication rather than at some later date. Even if the accused in the publicised trial eventually pleads guilty or even dies before the trial, the publication can still be held in contempt.

The courts take into account a number of relevant factors in determining whether there is such a real possibility of prejudice, including the prominence of the item printed or broadcast; the images accompanying it; the time lapse between publication and likely trial; the social prominence of the maker of contemptuous statements; and the extent or area of publication. In other words, a prominent sensational account of an imminent trial published in a major newspaper in the very area from which the jury would be selected would be much more likely to be held in contempt than a sober account in a small community radio news bulletin in a provincial town, some distance from the likely trial venue. This should not be taken as advice to knowingly publish a contempt in such cases. On the contrary: there is a tendency for prosecuting authorities to charge all media outlets that published contemptuous stories at the same time as the main sensational item that prompted their action.

Internet and social media coverage complicates the matter of course – particularly when publishers from far afield are publishing into the very jurisdiction where the jurors and witnesses live.

Watch those images of the accused

In 1994 Time Inc., publisher of the magazine Who Weekly, and the magazine’s editor were both fined for publishing on its front cover a photograph of Ivan Milat, the man accused (and later convicted) of murdering seven backpackers.

The publication came in another crucial time zone—after Milat had been arrested and charged but before his trial. Identification was going to be a crucial issue. In finding Who Weekly in contempt, the NSW Supreme Court held that the photograph tended to interfere with the due course of justice in the prosecution of Milat. It ran the risk of polluting the recollection of witnesses in that they may not be able to distinguish between what they had witnessed at the crucial time and their recollection of the image in the photograph.

While it was unlikely to have influenced the two key witnesses, who were overseas at the time of publication, the photograph ran the risk of affecting the testimony of witnesses who had not yet come forward. Even if the publication prompted new witnesses to contact the police, their testimony would be questionable because it had been influenced by the photograph.

The court ruled that publication of a picture of an accused person would normally be regarded as carrying a risk of interference with the due course of justice, unless the identification were so clear-cut that neither party would dispute it.

And don’t think that because everyone else is doing it you’ll be safe. In the Mason case in 1990 the NSW Attorney-General charged two newspapers and four television stations with contempt over their coverage of an alleged murderer’s confession to police after he had been charged, but before the trial. The outlets with the less sensational reports attracted lower fines ($75,000 as against $200,000), and the question arises: would they have been charged at all if their competitors had not published these more sensational accounts?

It is vital that media outlets work within these time zone restrictions when reporting on newsworthy cases like this one.

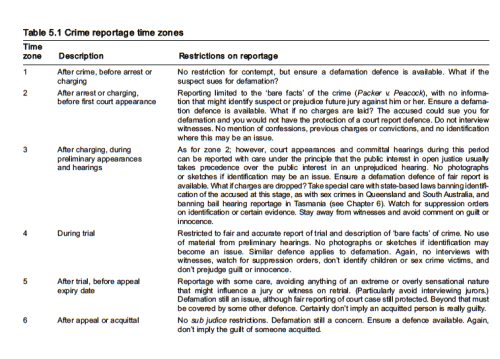

Table: Crime reportage time zones, from Pearson, M. (2007) The Journalist’s Guide to Media Law (3rd ed, Allen & Unwin, Sydney)

Disclaimer: While I write about media law and ethics, nothing here should be construed as legal advice. I am an academic, not a lawyer. My only advice is that you consult a lawyer before taking any legal risks.

© Mark Pearson 2014

What about th Rogerson case. Media waiting. They never give publicity to mothers who kill their children.

I totally agree, Mark. I couldn’t believe this week’s Sunday Mail cover story with its full account of the alleged tape recorded evidence in the ‘girl off the balcony’ case at Surfers Paradise. Maybe the C-Mail is counting on its support of the State Govt in its legal policies and the appointment of the Chief Justice to shield it from any contempt proceedings.

Thanks for your insights here, Frank. Great to see a ‘never really retired’ journo following with such interest. Cheers, Mark

Thanks Mark – we will be using your comments this week in Media Law and Ethics at ECU as this case has caught our eye as well!