By MARK PEARSON Follow @Journlaw

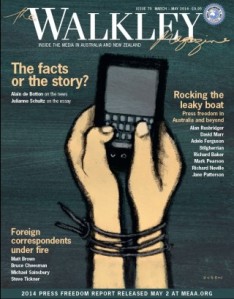

* This article was first published as ‘Terror on the books’ in the Walkley Magazine on May 29, 2014.

More than 50 anti-terror laws have been introduced by the Australian government since the September 11 attacks in the US in 2001, and they continue to impact on our coverage of national security issues and place journalists and their sources at risk.

No Australian journalist would want to see lives lost in a terrorist attack, but there is evidence that existing laws give police, security agencies and the courts too much power in monitoring media activities and suppressing reports that are in the public interest. Two major reports now confirm some of these existing laws are over-reaching.

The long overdue Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Review of Counter-Terrorism Legislation was released in 2013.

As well as recommending changes to basic definitions of terrorist threats and harm, it proposes there be more opportunity for judicial reviews of the agencies’ search and seizure powers, and introducing some safeguards to the control order system (a control order restricts where a person goes and who they can meet).

The committee suggested that the communications restrictions be eased to allow a person subject to a control order access to a mobile phone, a landline phone and a computer with internet access.

Most importantly for journalists, the review recommended the repeal of Section 102.8 of the Criminal Code dealing with “associating with terrorist organisations”. This reform would put beyond any doubt the likelihood of a journalist being convicted of this serious offence by just undertaking normal reporting duties.

Another major report came in November 2013 from Bret Walker SC, the Independent National Security Legislation Monitor (INSLM). It was his third report since being appointed to the review role in 2011.Walker repeated his earlier recommendation that ASIO’s questioning and detention warrants should be abolished and suggested improvements to the definition of a “terrorist act”.

He called for a simpler system of listing terrorist organisations and inserting an exception to the “associating with terrorist organisations” provisions for humanitarian groups such as the Red Cross.

While both reports focused on issues of natural justice and human rights, neither the COAG review nor the INSLM addressed the stifling of journalism in the anti-terror laws.

Sadly, there was little in the way of media lobbying to do so either. The COAG counterterror review received 30 submissions which it posted to its website, none of which were from media-related companies or journalism or free expression organisations.

The ripples of international security operations were also felt in Australia. In 2013 the Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance wrote to Prime Minister Tony Abbott asking for a review of the extent of metadata surveillance conducted by governments in the wake of former US National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden’s revelations.

There was good reason to be concerned. At least three cases in recent years have shown how the confidentiality of journalists’ sources can be compromised by surveillance by security agencies or anti-terror operations.

The retrial of “Jihad” Jack Thomas on terrorism charges in 2008 was based partly on interview materials gathered by Sally Neighbour from Four Corners and The Age’s Ian Munro and subpoenaed by the prosecution.

It emerged in the trial that up to 20 telephone calls between Neighbour and Thomas had been monitored by an ASIO agent.

The issue of confidentiality of whistleblowers’ identities also arose in the aftermath of the convictions of the Holsworthy Barracks bomb plot conspirators in 2011. The Australian had published an exclusive account on the raids in the hours before they occurred. (The three convicted plotters lost their appeals against their 18-year jail sentences last year.)

The Australian’s Victoria Police source, Simon Artz, paid for his leaks to the newspaper in the Victorian County Court with a four-month suspended sentence for unauthorised disclosure of information.

It was not a good year for whistleblowers internationally. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange is holed up indefinitely in Ecuador’s embassy in London as he avoids extradition to Sweden on sex charges (and feared extradition to the US over security leaks). His US Army source – Private Chelsea (formerly Bradley) Manning – was sentenced by a military court to 35 years in jail for leaking classified documents. Meanwhile, Edward Snowden had fled to Russia to avoid prosecution over his leaks.

The whistleblower’s revelations about the extent of government surveillance continue to cause embarrassment, including in Australia where Prime Minister Tony Abbott reacted by attacking the ABC over its reportage. In an interview in early 2014, Abbott voiced his disapproval that the ABC had run stories about security services eavesdropping on Indonesian leaders’ phone conversations, a fact revealed by Snowden’s leaks.

The ABC then faced an “efficiency study”. It seems the Abbott government’s approach is to put the budgetary microscope on the ABC’s operations rather than wind back national security laws in the interests of media freedom.

The suppression of reporting on terrorism-related trials or evidence tendered in national security cases is an ongoing issue. The use of a closed court – combined with government media management – was central to the misplaced prosecution of Gold Coast Hospital registrar Dr Mohamed Haneef in 2007.

More than 30 suppression orders under anti-terror powers were imposed during the Benbrika trials in 2008 and 2009. In that case, Abdul Benbrika and 11 other Muslim men from Melbourne were charged with intentionally being members of a terrorist organisation. Their arrests in 2005 followed Operation Pendennis, a 16-month surveillance operation by Victoria Police, the Australian Federal Police and ASIO.

While by 2014 legislation covering suppression and non-publication orders had been introduced into only the Commonwealth, New South Wales, Victorian and South Australian jurisdictions, it appears that other states and territories are following suit to harmonise the laws.

© Mark Pearson 2014

Disclaimer: While I write about media law and ethics, nothing here should be construed as legal advice. I am an academic, not a lawyer. My only advice is that you consult a lawyer before taking any legal risks.