By MARK PEARSON

Co-author Mark Polden and I are in the final stages of production of the fifth edition of The Journalist’s Guide to Media Law, to be published later this year.

We are re-engaging with the print medium as we apply our eagle eyes to the final hard copy galley proofs – our last chance for amendments and updates – before it goes to the printer for the production process.

Much has changed since our last edition in 2011, particularly in the fields of news media, communication technologies and practices, tertiary education and the law. We have reshaped and updated this edition of the book to accommodate those developments.

The book is still titled The Journalist’s Guide to Media Law, but its new subtitle—‘A handbook for communicators in a digital world’—encapsulates the seismic shifts that have prompted our considerable revisions. Our target audience has broadened with each edition as technologies like the internet and social media have combined to transform journalism and its allied professional communication careers. Thus our prime audience of Australian journalists working for traditional media outlets has widened to embrace public relations consultants, bloggers, social media editors and new media entrepreneurs, as they fill new professional occupations dealing with media law, once the domain of mainstream reporters and editors. Crucial questions which recur through the book include: ‘What is a journalist?’, ‘Who is a publisher?’, ‘How does media law affect this new communication form?’ and ‘Who qualifies for this protection?’ Some of the answers are still evolving, as legislators, the judiciary and the community grapple with the implications of every citizen now having international publishing technology literally at their fingertips on mobile devices.

Such shifts have prompted major new inclusions in the content of the book. So much publishing now transcends Australia’s borders via social media, blogs and other online platforms that we have expanded this edition to contain many more international comparisons and cases. This has been accommodated by reducing some of the forensic examination of precise legislation in various Australian states and territories, found in previous editions. Instead of attempting to document every statutory instrument in all nine Australian jurisdictions, we have directed readers to the resources that contain those details.

All of this has necessitated design and pedagogical changes to the book’s format and contents. While the chapter structure is generally in accord with previous editions, there are new sections within the chapters addressing these issues. Their order varies slightly according to topic, but most chapters now include some key concepts defined at the start, some international background and context to the media law topic, a more detailed account tailored to Australian legislation and case law, a review of the ‘digital dimensions’ of the topic with special focus on internet and social media cases and examples, an account of self-regulatory processes if they apply to that topic, some tips for journalists and other professional communicators for mindful practice in the area, a nutshell summary, some discussion questions, and relevant readings and case references.

The introduction of ‘tips for mindful practice’ encapsulates the authors’ aim that professional communicators need to build into their work practices and routines an informed reflection upon the legal and ethical implications of their reportage, commentary, editing, publishing and social media usage. This approach is explained in greater detail in Chapter 2, but it essentially links safe legal practice and the responsible and strategic use of free expression with the personal moral framework and professional ethical strictures of the digital communicator—whether a journalist, public relations consultant, media relations officer or serious blogger.

Those changing roles are reflected in a new final chapter, Chapter 13, which deals with the law of PR, freelancing and media entrepreneurship. It replaces a chapter on self-regulation in earlier editions. (The role and application of the various industry regulatory, co-regulatory and self-regulatory bodies, such as the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) and the Australian Press Council (APC), are now introduced in Chapter 3, but they are then referred to in the chapters where their functions and decisions seem most relevant). We saw this area of media law as significant because those who occupy those roles are now grappling with special dimensions of media law—and several other legal topics relevant to their work—and deserve a new chapter dedicated to their roles and the legal dilemmas that are emerging in relation to them. The chapter also reflects the fact that many former journalists are now working in these allied occupations, and that student journalists need to start their careers with a broad understanding of the legal considerations which govern allied professional communication industries.

The sheer pace of change in all areas of media law is astounding. Many changes were mooted as this edition was going to press—including important developments in the laws of privacy, copyright, hate speech and court reporting. Rather than render the book dated as soon as it is printed, we have opted to use co-author Professor Mark Pearson’s journlaw.com blog (this one!) as the venue for updates to material, and have built several mentions of that resource into the chapters and discussion questions.

Apart from an array of new cases and examples—many from the international arena and many more from social media—some highlights of important new content covered in this edition include the following:

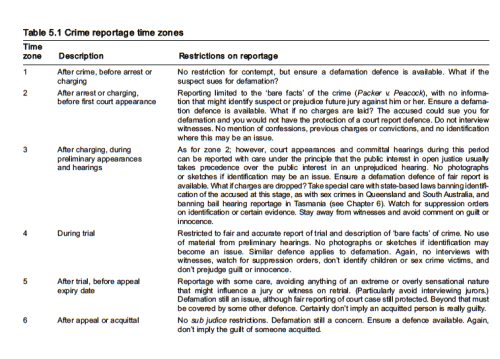

- There are significant cases on increased statutory powers, allowing courts to make suppression and non-publication orders, and on the relationship between free speech, open justice and the right of parties to settle disputes privately. Recent cases at the borderline between ridicule and defamation, and on the application of freedom of information laws to immigration detention centres are included, as are cases on the application of sub judice contempt to internet content hosts and ‘celebrity’ claims of privacy invasion.

- Recommendations of the ALRC on copyright reform are included, together with a discussion of the new copyright fair dealing defence that applies to satire. The book presents a wide range of examples, across different legal categories, relating to the use of the internet and social media, which will be of growing importance for current and future professional practise in communication, reportage and media advice.

- A separate chapter on secrets (Chapter 9) covers the new journalists’ shield laws and their relevance to micro-bloggers and non-traditional publishers.

- Chapter 10, on anti-terrorism and hate laws, includes the recommendations for reform of anti-terror laws and discusses the high-profile Andrew Bolt case and related proposals for reform of the Commonwealth Racial Discrimination Act 1975.

- The recommendations of the Leveson Inquiry in the United Kingdom, and the Finkelstein Inquiry and Convergence Review in Australia, are subjected to critical analysis in view of their potential impact upon notions of a free press.

There is also an increased emphasis on real-time reportage, as the traditional print media increase their online presence and depth of click-through coverage in a 24/7 news cycle, with concomitant risks in the areas of defamation and contempt in their own work and that of third-party commentators on their websites and social media pages.

Without going into exhaustive detail on all of these matters, the book remains true to its original aim: to provide professional communicators and students with a basic working understanding of the key areas of media law and ethical regulation likely to affect them in their research, writing and publishing across the media. It tries to do this by introducing basic legal concepts while exploring the ways in which a professional communicator’s work practices can be adapted to withstand legal challenges.

In designing this edition, we have tried to pay heed to the needs of both professional communicators and media students. The book is best read from front to back, given the progressive introduction of legal concepts. However, it will also serve as a ready reference for those wanting guidance on an emerging problem in a newsroom or PR consultancy. The cases cited illustrate both the legal and media points at issue; in addition, wherever possible, recent, practical examples have been used instead of archaic cases from the dusty old tomes in the law library. Rather than training reporters, bloggers and PR practitioners to think like lawyers, this book will achieve its purpose if it prompts a professional communicator to pause and reflect mindfully upon their learning here when confronted with a legal dilemma, and decide on the appropriate course of action. Often that will just mean sounding the alarm bells and consulting a supervisor or seeking legal advice.

Of course, the book is not meant to offer actual legal advice. Professional communicators must seek that advice from a lawyer when confronted with a legal problem. The most we claim to do is offer an introduction to each area of media law so that journalists, PR consultants and bloggers can identify an emerging issue and thus know when to call for help.

Booktopia is offering pre-orders on their website: http://www.booktopia.com.au/the-journalist-s-guide-to-media-law-mark-pearson/prod9781743316382.html

Disclaimer: While I write about media law and ethics, nothing here should be construed as legal advice. I am an academic, not a lawyer. My only advice is that you consult a lawyer before taking any legal risks.

© Mark Pearson 2014